The UK pioneered the use of radioactive materials and developed a whole new industry for the ‘nuclear age’. A world-leading nuclear sector has emerged and has continued to deliver benefits for many decades. Nuclear power still provides around 15% of the UK’s electricity and nuclear technology is also used in industry, medicine, and defence.

As a consequence though, there is a legacy of both higher-activity radioactive waste and low-level waste that has to be dealt with and all of it requires careful management, with safety the number one priority. Disposing of even low-level radioactive waste is a long-term mission. We must think about how it impacts people and the environment today and how it will impact them in hundreds or even thousands of years too.

This means ensuring the radioactive waste we generate is safely and securely managed now and permanently disposed of when facilities are ready for closure. There are a range of solutions available, including the existing Low Level Waste Repository site and for the most hazardous radioactive waste, the UK is now planning to construct a Geological Disposal Facility (GDF).

The Low-Level Waste Repository, based near the village of Drigg, in West Cumbria, has been the main disposal site for the UK’s low-level radioactive waste since 1959. To date it is the only facility that is permitted to receive all categories of LLW in the UK and receives low-level solid waste from a range of stakeholders such as the nuclear industry, the Ministry of Defence, non-nuclear industries, and educational, medical and research establishments. Initially, this waste was placed into clay lined trenches and covered over with an interim cap. Since the 1980s waste has been received in steel containers, which are filled with grout and placed in engineered concrete vaults ready for final disposal.

Managed by Nuclear Waste Services (NWS) and led by the Waste Operations team, the LLW Repository site’s role is to ensure that Low-level Waste generated in the UK is disposed of in a way that protects people and the environment. NWS provides integrated radioactive waste treatment, logistics and disposal services to support the UK’s radioactive waste programmes. It has delivered a step change in the management of radioactive waste in the UK and has been providing services and expertise to help manage radioactive waste in accordance with the Waste Hierarchy for 14 years.

The importance of capping

With a 65-year legacy of receiving low-level radioactive waste, the site is now ready to transition to final disposal, marking a key phase in the repository’s lifecycle. Currently, the focus for the repository site is on Capping Operations.

Capping is a key part of the disposal lifecycle and will provide an engineered protective cover over legacy disposal trenches and vaults, which house low–level radioactive waste – making it ready for final disposal and permanent closure. The end result will be to install an engineered cap of up to 15 metres thick over the legacy trenches and Vaults when they are finally closed.

Comprising of multiple layers of different materials, this ‘cap’ will permanently protect people and the environment. Primarily by layering natural aggregates, such as gravel, sand, stones and rocks, as well as engineered materials like geotextile fabrics and bentonite-enriched soil, these multiple layers of material will gradually form a dome-like shape over the trenches and vaults. This will serve as an impermeable barrier above the waste and once complete to anyone passing by will simply look like a small hill, planted and grassed, blending into the adjacent SSSI on the edge of the Lake District fells.

From an engineering standpoint, this is quite an undertaking. When full construction begins, it will involve gradually bringing a large amount of materials to site by rail using existing rail sidings. This material with then be moved onto the capping site and placed precisely in the various layers needed to build up the protective engineering.

It’s vital to be able to build the cap in layers because each layer will provide a different function. Some will allow gases like methane to escape, others will help form the right shape of the cap, and some will help water drain away.

Using natural materials builds confidence in the cap working for longer as evidence obtained over centuries of construction activities has shown that these materials have proven longevity. There will also be a layer to deter human intrusion, made up of large stones. This layer is designed to discourage future generations from digging through the cap, in the event that societal evolution means the understanding of what is under the cap has been lost.

Constructing the cap protects the environment and people now and in the future from radioactivity. It will allow us to keep the waste dry and puts in place key requirements from our Environmental Safety Case and fulfils our obligations under the Repository’s Environmental Permit from the Environment Agency (EA).

The journey to capping goes back over a decade to the development of the 2011 Environmental Safety Case. Since then, the design of the cap has matured and NWS has obtained planning permission to build it. In addition, NWS has completed a multi-million pound ‘enabling works’ phase (to ensure the Repository site is ready for construction activities), as well as procuring the contract for the first stage of the works.

The works are scheduled to get underway in February 2025. Of course, a huge project like this requires a high degree of collaboration and working closely with a wide range of stakeholders, particularly the local community, to bring the capping programme through to completion.

One of the key stakeholders is the Environment Agency which is helping to ensure compliance with environmental standards and the conditions of the Environmental Permit, along with Cumberland Council as the local authority, which has provided planning consent and set conditions for the site development.

A GDF for HLW

NWS is also responsible for delivering a GDF for the UK, providing a permanent solution for the most hazardous radioactive waste that cannot be sent to the Drigg Repository or treated. Currently this waste is housed in around 20 above-ground facilities across the country – this is not sustainable as these facilities will need to be maintained and replaced for many thousands of years. When built, a GDF will also support the government’s plans to achieve a clean power system by 2030 and to accelerate to net zero across the wider economy – nuclear will play an essential role in the future age of clean electricity. Investing in a GDF now also removes the burden of managing the UK’s nuclear legacy from future generations. As a result, UK Government policy is to establish a GDF for the permanent disposal of the country’s most hazardous nuclear waste. This globally accepted solution will in time remove the need for any kind of human intervention in handling the most hazardous nuclear waste.

While the development of a GDF will bring huge benefits to the environment by providing a site for the safe, permanent disposal of nuclear waste, it will also bring benefits to the local host community – including community investment funding, significant investment funding from the government, jobs, infrastructure and transport. A GDF is therefore also a unique opportunity to boost a host region’s economy for many generations.

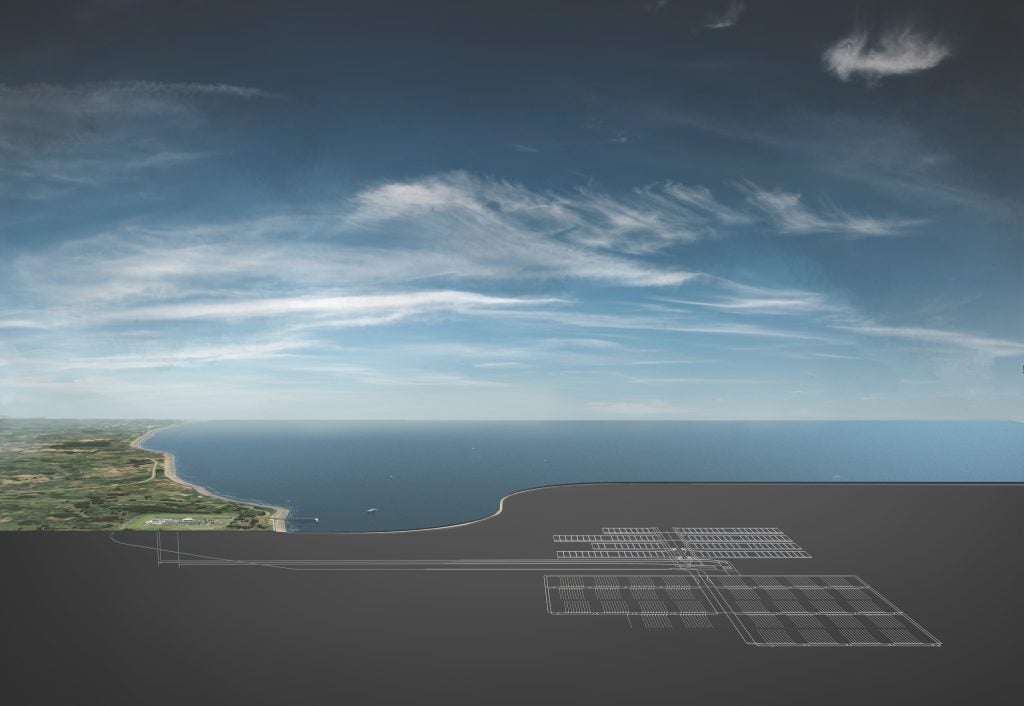

Such a facility will only be built where there is both a suitable site and a willing host community. Three communities across England, two in Cumbria – Mid Copeland and South Copeland – and one in Lincolnshire around Theddlethorpe are engaging in the programme to learn what hosting a GDF could mean for them. When a suitable site is selected, a process which could take 10-15 years, a decision to develop a GDF could not be taken until the potential host community has had a say and given consent through a Test of Public Support. Studies, that got underway in 2023, will now help to identify the suitable locations to begin further investigative work, such as drilling deep boreholes, to understand the geology and help ensure a GDF can be constructed, operated, and closed safely and securely. A decision on the first community to progress to deep borehole investigation and receive increased community investment as a result is expected to be shared with Government by 2026-2027.

Construction will only start on a GDF when a suitable site has been identified, the host Community has confirmed its support, and all the necessary consents and permits have been obtained. GDF borehole investigations are expected to commence around 2029-2030 and the latest planning assumption is that a GDF will be available for intermediate level waste in the 2050s and high-level waste and spent fuel from 2075.

The final cap: what completing the programme will mean

The UK has been producing and managing radioactive waste for many decades and will continue to do so for many more. Nuclear power is a key part of the country’s low-carbon energy mix and essential to securing our energy supply in the future. We also use radioactive materials in the UK’s defence, research, medical and industrial sectors.

Through the work done to divert waste from the repository NWS has extended the life of the repository, ensuring there is enough capacity to deliver the NWS waste disposal mission.

Effective treatment of radioactive waste reduces overall waste volumes and helps makes the radioactive waste permanently safe, sooner. NWS are involved in a number of crucial long-term activities to support this goal, including helping waste producers manage their waste in the most sustainable and cost-efficient way. The treatment and alternative disposal routes include sending the waste to permitted landfill, super compaction, combustion and metallic treatment.

The organisations and businesses which produce the waste have also been doing much more to cut the amount of material they send to the repository in West Cumbria, with 98% now being treated, reused and recycled. This has seen the number of containers that come to the site every year reduce from 700 to around 20 or 30.

Putting the final cap on the vault and trenches at the Repository is another one of these measures to make radioactive waste materials permanently safe. By procuring, importing and emplacing thousands of tonnes of capping materials in line with planning conditions and quality requirements, permanent closure of this important disposal site will be achieved, ensuring environmental protection and safety for generations to come.