The fusion industry has now succeeded in attracting more than $7.1bn of investment, with more than $900m of that coming in the last year alone. This is the conclusion of the latest annual report from the Fusion Industry Association (FIA).

Andrew Holland, the FIA’s Chief Executive Officer, tells NEI: “Significant amounts of money this year of over $900m indicates that investors are still bullish on the growth of this technology, even as it has been a difficult environment to raise capital in lots of tech industries.”

With both public and private investors pumping an additional near billion dollars into the companies working to commercialise fusion technology, the report notes that as part of the year’s funding, total public funding increased by 57% to reach $426m, showing governments increasingly see public-private partnerships as key to commercialising fusion. In contrast with previous annual assessments, investment is split roughly 50-50 between public and private finance sources.

Public-private finance split changes

The increase in public funding directed into private companies has risen from $271m in 2023 to $426m in 2024 from direct grants or cost-shares in public-private partnerships. The report suggests that this increase in government investment, which is likely an undercount as some things go unreported, not only reflects a heightened interest from national governments, but also signals a strategic choice by a growing number of governments that it will be business, not government, that will deliver the pilot plants that demonstrate fusion as a viable energy source. The report concludes that while fusion will be commercialised by private companies, public programmes will continue to lead the world with groundbreaking scientific research and enabling technology. The report argues that while competition is good among companies for spurring private sector innovation, there is no need to pit government programmes against private companies as the two must support each other. As fusion advances towards commercialisation, the consistent and growing investment from both private and public sectors is vital for overcoming the scientific and engineering challenges that remain, the report observes.

As Holland says: “We’ve seen a lot more public finance going into private companies and that is new.” He also highlights multiple government initiatives designed to support the sector with finance and other support mechanisms. “There are new programmes that have been put in place in multiple countries. The United States has its Milestone-Based Fusion Development Program, Germany has instituted a new programme though funding hasn’t started flowing yet so we’ll see more coming in that space, the UK and even the European Union is getting a plan put in place, Japan is as well so we see this as not only an important signal for this year but that it’s going to be a continued area of growth in the future.”

In June 2024 the United States announced eight companies had signed contracts with the Department of Energy to deliver comprehensive pilot plant designs under its programme. The German government’s new ‘Fusion 2040’ scheme will invest directly into private companies. The Japanese government’s ‘Moonshot’ program, the UK’s new ‘Fusion Futures’ programme and the European Union’s recent effort to create a consortium that will define how it will invest in private fusion by 2026 are all recent examples of public-private partnership efforts.

This is important given the changing characteristics of the investment landscape. Holland points to previous FIA annual reports which show a trend of declining investment in the sector but Holland nonetheless remains buoyant, saying: “The year before it was over $1bn and then the year before that was well over $2bn though that funding came predominantly at the end of 2021, which was zero interest rate times and investor money flowed pretty freely. Since then, we’ve seen inflation come in and a lot of other issues so that the total [investment] number is down but I can also say from investors that very significant amounts of investment have not yet been publicly announced.”

He also points to recent announcements which aren’t yet included in these figures. For example, South Korea recently announced a government project worth KRW1.2 trn (US$878m) focused on harnessing fusion through a private sector-led fusion ecosystem. The initiative is separate from K-STAR and South Korea’s ITER contributions and aims to foster public-private collaboration that can integrate the engineering capabilities of the private sector with the scientific research expertise of public institutions.

“We only report when the money actually flows into the company so the fact that the Koreans announced a new $900m programme we wouldn’t report. Usually, it takes time to set up a programme, complete applications and select those companies to move forward. In the US that took two years between the time the milestone programme was announced and when it was finally signed and done.” He continues: “We’re seeing that growth in public investment pushing into these technologies perhaps coinciding with a slight downturn in private capital. That level of support is there and that trend is continuing beyond the window of this particular report.”

Confidence grows

With total funding now more than $7bn, even in the face of continued challenges in raising capital for deep technology ventures, the investment underscores growing confidence in fusion technology’s potential on a timescale relevant to investors. And, at the same time as fusion investment structures are evolving, industry confidence is also on the rise. The Global Fusion Industry in 2024 report, FIA’s fourth annual assessment, surveyed 45 private fusion companies. This is up from the 43 companies which contributed last year with three new entrants, while one company withdrew its efforts to commercialise its own fusion power plant and instead became a supplier to fusion companies, remaining active in the fusion industry as a key partner. This is translating into increased industry optimism that fusion power will be grid connected on a similar time frame to Small Modular Reactor (SMR) technologies, around the mid-2030s.

“The very large majority of companies, nearly 90%, report that they expect to see fusion energy on the grid in the 2030s or before and 70% expect to see fusion energy on the grid in 2035 or before. This is a decadal time frame, an ambitious time frame. It’s not companies saying we wish that this will happen this is them saying we expect to see it happen,” observes Holland.

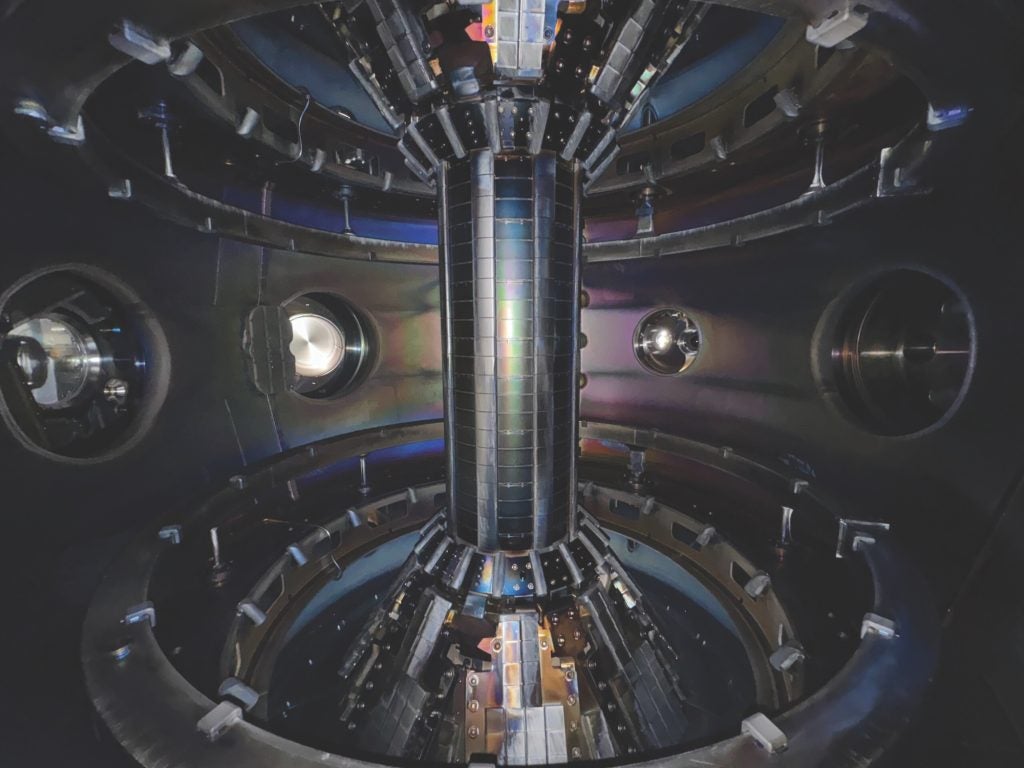

These timelines are little changed since the FIA’s annual report was first produced in 2021 “The industry is hitting its own milestones, and remains on track,” Holland says. He continues, adding: “There is definitely a sentiment that there are certain things that will be solved in the near term, and it is what people think of as the harder parts of fusion – the actual plasma physics and plasma containment. We’ve seen optimism both in this report and anecdotally that they’re confident that when companies build the machine it will work.”

However, as solutions are found to some of the biggest physics issues new challenges become more prominent. “The areas of challenge that have been identified include things that are needed for the demonstration plants themselves. To make a power plant you have to be able to do the whole rest of the balance of plant, the fuel cycle, you have to have resilient materials. These things are still identified as a challenge and companies are becoming more aware of it as they are confident that they can build a machine that will demonstrate fusion.”

Nonetheless, while the companies themselves have always been confident that they could achieve commercial fusion, the FIA argues that investors and other stakeholders are also increasingly feeling that confidence in eventual success too. And, while that is not necessarily being reflected in more investment from the private sector, Holland suggests this is indicative of a milestone-based investment structure that is prevalent in the fusion industry, saying: “I think what we’re going to see investment follow milestones, investors are basically saying show us results and then that will unleash the next stage.”

Key players and technology choices

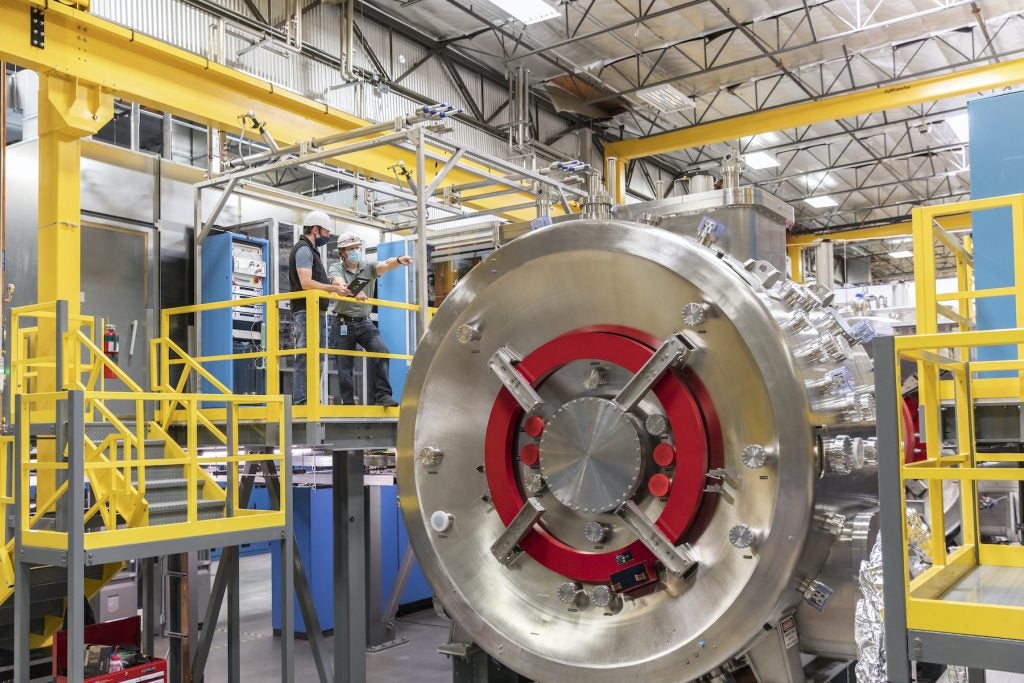

The report highlights that the total funding figure came from a wide range of investments across many of the 45 fusion companies, including notable deals such as $100m for Xcimer, $90m for SHINE, and $65m for Helion. Fusion companies which have recorded $200m of investment or more include TAE Technologies ($1bn+), General Fusion, Tokamak Energy, Zap Energy, Commonwealth Fusion Systems ($2bn+), Helion, SHINE and ENN.

Given the current state of fusion development there is no clear or even emergent technology leader. Holland comments: “If you look at the numbers it’s very clear that historically the most funding has gone into magnetically confined fusion. Whether it’s tokamaks or stellarators or like TAE’s field reverse currents, the bulk of the funding has gone into that. That said, significant amounts of new funding have recently gone into laser inertial fusion so what I extrapolate from that is that the market hasn’t really decided yet. We are not at a time when there’s been a down selection and in fact seeing a proliferation of different technologies. Of the 45 companies, it’s almost 45 different ways to get to commercial fusion and there might be more.”

The FIA saw a leap in the number of companies between the second and third reports (2022-2023) where the figure jumped from 33 to 43 but while the increase in companies has stabilised there are still clearly potential opportunities for many more new entrants.

Beyond the technical and financial challenges another potential issue faced by both fusion and fission nuclear power sectors is recruitment and securing the staff to not only build but operate the power plants of the future. Again, though, Holland is confident this issue can be resolved:

“We absolutely have to have the people to be able to do this and we think that is a solvable problem. The fusion workforce is really downstream of the whole STEM, science, technology, engineering, manufacturing workforce so those problems are well known and understood around the world. We’re convinced that if you can address those problems then fusion is actually a relatively small part for the next decade or so but then it will get to be significant when we get into the scale up and global deployment.”

The FIA records the fusion workforce expanding by around 1000 people a year on average, which is adequate to meet the needs of the industry for the next several years, but there has been a substantial increase in recruitment since the last report. Recording a 34% increase since 2023 (1,034 more employees), and up nearly 300% since 2021 (3,011 more employees), nearly half of those employed are engineers (48%), a quarter are scientists (25%), and a quarter are in other roles (27%).

The report notes that the fusion industry workforce is predominantly of scientists and engineers, who together constitute approximately 73% of all employees. This high concentration of technical expertise, the report says, is indicative of the intensive research and development efforts required to advance fusion technology. Furthermore, the sector’s ability to consistently increase employment underscores its resilience and adaptability in a rapidly evolving technological landscape. Workforce needs will continue to grow, and the industry has adopted an “all hands on deck” approach to hiring skilled employees from diverse backgrounds and outside the traditional scientific sectors.

“We’ve got over 4,000 people in fusion companies right now, but what we’re aiming for really is manufacturing at the scale of Boeing or Airbus or large auto manufacturers. In the long term that is the plan, but right now it is not necessary”. He also points to interest from governments, universities and other stakeholders in getting the STEM workforce in place. In particular he points to local government as a key driver, saying: “Regional governments are often very interested in supporting workforce development in multiple ways because if you have the workforce then you attract the companies”.

Pointing to global winners in the fusion race

Considering the geographical concentration of fusion efforts, the US remains the global leader for commercial fusion with 25 companies recorded in the survey. The US is followed by the UK, Germany, Japan, and China, all nations with three companies each. Switzerland is a new entrant, now hosting two fusion companies, while Australia, Canada, France, Israel, New Zealand, and Sweden all have one each. However, the specific number of companies is not necessarily a reflection of the national fusion efforts that are underway.

Holland explains: “If you look at the numbers the largest number of companies and the largest amount invested in those companies is into American companies, it’s about $5.3bn of that $7.1bn, but then the second country for total amount invested is China. There are three Chinese companies mentioned in the report and if you add up the total invested into those three companies it’s over $500m. If you compare those companies that are serious with a very serious national programme I think that there is an emerging geopolitical race. It’s not just money, the Chinese are able to build very fast they don’t have to go through the rigorous planning permission processes. Government can make a decision and move quickly and historically we used to be able to do that in the West but haven’t recently.”

Despite sounding a note of potential caution, overall the message is one of growing confidence. As Holland concludes: “Continued growth in investment and employee numbers are exactly what we should be seeing in a maturing industry and underscores confidence in fusion technology’s potential. With government policies shifting to direct more public funding into private fusion companies, the major players are aligning behind a shared goal.” Sustainable and abundant energy from fusion is looking increasingly attainable.