We can all agree that the nuclear industry faces serious challenges. Here we are, decades into the climate crisis and a couple of years past a global energy shock yet at the moment nuclear’s share of global electricity continues to trend down, not up.

There are signs of better times ahead as countries review their energy mixes and start planning in earnest for a zero-carbon future, but the elder nuclear industry hands have seen this kind of excitement before. They know that momentum for new nuclear can fade as external factors change and as the ‘issues’ come sharply into focus.

Even where the industry enjoys strong political support, if there’s no way to overcome the obstacles that stand in the way of development then few projects will actually emerge as a physical reality. With this in mind, the apparent lack of progress on roadblocks over the years is troubling and may prevent the industry from making the most of the favourable winds that are currently blowing.

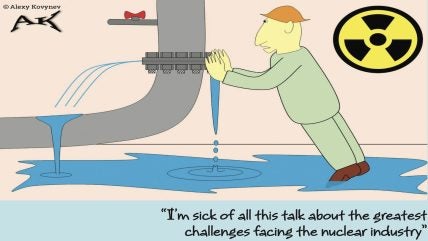

The issues facing nuclear expansion are no mystery. While they may come in different forms, with varying levels of sophistication depending on who is articulating them, these days they almost always boil down to two things – public acceptance and economics.

Which leads to an interesting thought experiment. Granted, both have to be addressed, but if you could magically fix only one of these issues with a snap of your fingers, which would it be, which issue has done most to diminish industry prospects over the years, and what is acting as a hand-brake on it now?

Perhaps surprisingly, there is no definitive answer and industry experts seem to be split evenly into two camps.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that people are biased by their education, experience and work areas. For example, if you have a business background or regularly talk to the finance community then of course it’s economics that is the fundamental problem!

The thinking here goes that if the nuclear industry could consistently demonstrate on time on budget construction then the orders would come streaming in. Public acceptance issues would melt-away in the face of lower energy bills. Reluctance from important stakeholders in government and the finance community would be steam-rolled by profitable returns. The mountain-sized challenge of securing project financing from banks and investors would shrink down to a much more manageable boulder – or in the case of SMRs, a pebble.

For those in this camp, the failure of the nuclear industry to expand (in Western countries at least) is due overwhelmingly to high capital costs, or even more so the well-documented failure to control construction risk at project after project. This view is essentially an implicit mea culpa. It is tacit acknowledgment that the industry has none other than itself to blame for the situation that it now finds itself in.

On the face of things, this is convincing. After all, money is what makes the world go round, and we all have to deal with this on a daily basis. If you are money-oriented with the decisions in your own life – and certainly most highly- paid industry professional will be – then it makes sense that you expect everyone else to be as well. As a commercial enterprise, nuclear plants must make financial sense or companies simply won’t build them.

Those nuclear professionals with a communication or public facing role may see the world differently. Of course, energy costs are important, but it is just one of a number of factors that Jane/Joe Smith tends to be affected by. For starters, she/he will certainly be worried about jobs and economic opportunities generally, or perhaps lack thereof. More generally though, there will be range of social, cultural and even gender-based values which influences their views.

Acutely aware of concepts such as cognitive shortcuts and risk perception, at the top of the list of factors standing in way of nuclear expansion for these nuclear professionals are the dread-risks associated with nuclear accidents and nuclear waste. In their eyes opposition to nuclear energy is essentially irrational. In fact it is often pretty darn emotional but this is not to say it is ‘unjustified’. Addressing such concerns purely with facts (or improved standards and performance) is unlikely to win people over. Indeed, no other energy industry has to contend with such deeply- seated fears.

Under this paradigm, our collective energy future is being determined by a fiery debate rather than a calm analytical conversation. There are well-funded anti-nuclear bodies that have had huge impact on the fate of the industry in many countries. These constantly chip away at political support, making sure that the policy and market reforms needed to make new nuclear viable never happen.

Rather than seeking to prove which mindset is ultimately right, the point is that there is quite a fundamental difference in approach between those in the ‘it’s the economics’ and ‘it’s public acceptance’ camps. Moreover, the priorities for action end up being very different. It is at least important to be aware of the competing paradigms.

An alarming observation is that those who think economics is the main issue often don’t seem to have much faith in industry communications and advocacy efforts.

This is likely why nuclear industry communication remains so woefully under-resourced compared to the other branches of the industry – especially those associated with engineering.

By contrast, probably every nuclear communicator agrees with the need to improve nuclear economics. There really is no denying that this is an issue its own right, and an additional barrier to nuclear energy acceptability.

Take a glance at Western energy media and it’s clear that economics has become the primary argument cited by opponents against new build. The question industry professionals have to wrestle with is how much of this objection is reasonable and fact-based, requiring navel gazing and improvement, and how much of it really calls for deeper understanding and action from decision makers and other stakeholders?

Looking at this issue from a slightly different angle, how much sense does it make to consider nuclear economics in isolation from the system risks and impacts of variable renewables and alternative decarbonisation pathways? How sensible is it to ignore the contributions to nuclear costs that are essentially controlled by governments, regulators and even NGOs (via lawsuits and objections).

In many ways the rise of the objection-from-economics can be considered a victory for the nuclear industry. It’s a welcome shift from the howls of ‘too dangerous’ and ‘polluting’ that marked the discourse of earlier decades.

Yet this claim to victory is also slightly disingenuous. If you were to scratch the surface of the anti-nuclear argument, how often would you find the dread risks of waste and safety lurking just beneath? The nuclear industry absolutely must continue to improve economics, but to do so at the expense of communication and outreach activities is foolish. Economics versus public acceptance is of course a false dichotomy.

In other parts of the world, this thought experiment is a diversion. In developing countries especially, the main challenge facing the development of nuclear energy is more accurately described in terms of perceived readiness, governance, non-proliferation and the willingness of established nuclear countries to partner with them. If one industry issue could be magically solved this one would likely have the biggest global impact on new nuclear development. However, ultimately there’s little doubt this would require addressing both the economics and public acceptance of nuclear power too.