The US Department of Energy (DOE), Washington State Department of Ecology (Ecology), and US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have finalised a landmark agreement that outlines a realistic and achievable course for cleaning up millions of gallons of radioactive and chemical waste from large, underground tanks at the Hanford Site.

Hanford, in Washington State, is home to 177 underground waste storage tanks – a legacy of nuclear weapons development and nuclear energy research during World War II and Cold War. These include 149 single-shell tanks (SST), and 28 double-shell tanks (DST), ranging from 55,000 to 1.265m gallons in capacity. The tanks are organised into 18 different groups called farms. Currently, the site’s underground tanks store approximately 56m gallons of radioactive and chemical waste.

The final agreement comes after the agencies sought and considered public and tribal input in 2024 on proposed new and revised clean-up deadlines in the Tri-Party Agreement (TPA) and Washington v USDOE consent decree. Following voluntary, mediated negotiations that began in 2020, also known as Holistic Negotiations, the agencies signed a settlement agreement in April 2024 with the proposed TPA and consent decree changes.

The agencies held a public involvement effort in spring and summer 2024 to obtain feedback on the proposed changes, which included a 30-day preview, 90-day public comment period, and three hybrid (both in-person and virtual) public meetings across Washington and Oregon. The agencies also offered consultation to the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Nez Perce Tribe, and the Wanapum Band.

The finalised changes uphold a shared commitment to the safe and effective cleanup of tank waste. Highlights include:

- Maintaining existing timeframes for starting treatment of both low-activity waste (2025) and high-level waste (2033) by immobilizing it in glass via vitrification;

- Using a direct-feed approach for immobilising high-level waste in glass, similar to the Direct-Feed Low-Activity Waste Programme;

- Building a vault storage system and second effluent management facility to support treating high-level waste;

- Retrieving waste from 22 tanks in Hanford’s 200 West Area by 2040, including grouting the low-activity portion of the waste for offsite disposal;

- Designing and constructing 1m gallons of additional capacity for multi-purpose storage of tank waste;

- Evaluating and developing new technologies for retrieving waste from tanks.

Under the settlement agreement, DOE also committed to refrain from applying its interpretation of what constitutes “high-level waste” when disposing of treated waste or closing tank systems at Hanford.

The agencies collected 185 comments during the public comment period, all of which were considered by the agencies prior to issuing a comment responsiveness summary and finalising the agreement. In response to comments received, DOE agreed to hold a 30-day review and comment period associated with the proposed plan for retrieving, grouting, and transporting some of Hanford’s low-activity tank waste for out-of-state disposal. Review this draft National Environmental Policy Act Supplement Analysis is anticipated to begin later this year.

The agencies revised the due dates for several of the proposed milestones to allow additional time for this public involvement process. One of these is the deadline for DOE’s decision on where to grout the waste, which is now the end of 2025.

Brian Vance, Hanford Field Office Manager: “This historic agreement, reached through years of negotiations with our Tri-Party Agreement partners from the Environmental Protection Agency and the Washington Department of Ecology establishes an achievable plan for our Hanford tank waste mission for the next 15 years. DOE also appreciates the time and effort that the public, stakeholders and Tribes took to review and provide comment on the agreement.”

Laura Watson, Ecology Director: “Cleaning up Hanford’s tank waste is critical for Washington state. With this final agreement, we’ve created a durable framework that will accelerate work while maintaining safety. More tank waste will get retrieved, treated, and disposed through 2040 and beyond. This is the best way to ensure surrounding communities and the Columbia River are protected.”

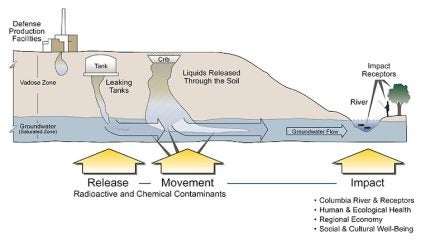

In the 1980s, groundwater contamination totalled about 80 square miles. Today, about 60 square miles of groundwater remains contaminated above federal standards — and the level of contamination has been greatly reduced for significant portions of that area.

There are no active nuclear production facilities; however, the site contains some of the nation’s most complicated nuclear and mixed dangerous waste, which must be cleaned up. DOE is required to maintain security and prevent unauthorized access to contaminated areas of the site. In the event of an emergency, Energy is required to effectively respond to protect human health and the environment.

State and federal governments monitor the Hanford site and the Hanford Reach of the Columbia River for contaminants, and inform the public of possible risks. Results are published in annual groundwater reports. Although the Columbia River basin covers parts of many states and tribal lands, DOE says the Columbia River meets all surface water quality standards. Water taken from the river by cities downstream is used for drinking water, and the cities that use Columbia River water comply with the federal Safe Drinking Water Act.

For the past few decades, the most dangerous radioactive and chemical waste has been and continues to be moved from single-shell tanks to safer double-shell tanks at Hanford. The waste will remain in the double-shell tanks until it can be moved to the Waste Treatment and Immobilisation Plant (WTP), which is under construction.

Once completed, the WTP will turn the high-level waste into glass, through vitrification, that will then be stored in high-grade stainless steel casks. Although still be radioactive, the vitrified waste will no longer be able to seep into or pollute the air, water, and soil. Without the retrieval and treatment of the tank waste, any leakage would eventually reach the Columbia River. WTP is critical in helping to clean up Hanford and in reducing the possibility of further threats to the environment and all who live and work near the Columbia River.

The single-shell tanks contain a mixture of saltcake and slurry that is both radioactive and chemically hazardous and comprises liquid mixed with solids. Some tanks have more waste than others, and the radioactive and chemical content can vary widely from tank to tank.

Liquid that rises to the top is called supernatant. It’s present in about 58 single-shell tanks. The total volume in those 58 tanks is about 228,000 gallons. An estimated 28.2m gallons of combined saltcake, sludge, and supernatant waste remain in the single-shell tanks.

DOE keeps an estimate of inventory in all the single-shell and double-shell tanks. There are three tanks that are actively leaking. The most recent announcement for T-101 was August 2024. For tanks B-109 and Tank T-111, Ecology issued an Agreed Order with DOE to both address these active leaks and future leaks from single-shell tanks.

Unless existing problems are addressed, the tanks will continue to corrode and develop leaks, and contaminants could eventually reach the Columbia River at very high concentrations. The Tri-Party Agreement requires 99% of waste be retrieved, or as much as can be, using multiple techniques. However, a more immediate concern is the waste that has already leaked from the tanks, contaminating the soil underneath. WTP is critical in helping to clean up Hanford and in reducing the possibility of further threats to the environment and all who live and work near the Columbia River.