US fusion energy tech startup Helion Energy has signed an agreement to provide Microsoft with electricity from its first fusion power plant. Constellation will serve as the power marketer and will manage transmission for the project. Helion said the plant is expected to be online by 2028 and will target power generation of 50 MW or more after a one-year ramp up period. The companies did not disclose financial or timing details of the power purchase agreement, or which Microsoft facilities would get fusion-generated electricity.

US fusion energy tech startup Helion Energy has signed an agreement to provide Microsoft with electricity from its first fusion power plant. Constellation will serve as the power marketer and will manage transmission for the project. Helion said the plant is expected to be online by 2028 and will target power generation of 50 MW or more after a one-year ramp up period. The companies did not disclose financial or timing details of the power purchase agreement, or which Microsoft facilities would get fusion-generated electricity.

“This collaboration represents a significant milestone for Helion and the fusion industry as a whole,” said Helion CEO David Kirtley. “We are grateful for the support of a visionary company like Microsoft. We still have a lot of work to do, but we are confident in our ability to deliver the world’s first fusion power facility.”

“Constellation is committed to innovation and supporting next-generation clean energy technologies to combat the climate crisis, and fusion would be a game-changer,” said Jim McHugh, Chief Commercial Officer at Constellation. “Combined with our hourly carbon-free energy matching solution, Helion and Microsoft are helping to build a future where carbon-free energy is the standard.”

Helion has so far raised more than $570m in private capital, with OpenAI CEO Sam Altman providing $375 million in 2021. Brad Smith, vice chair and president at Microsoft Corp, said in a news release that Helion's work "supports our own long-term clean energy goals and will advance the market to establish a new, efficient method for bringing more clean energy to the grid, faster."

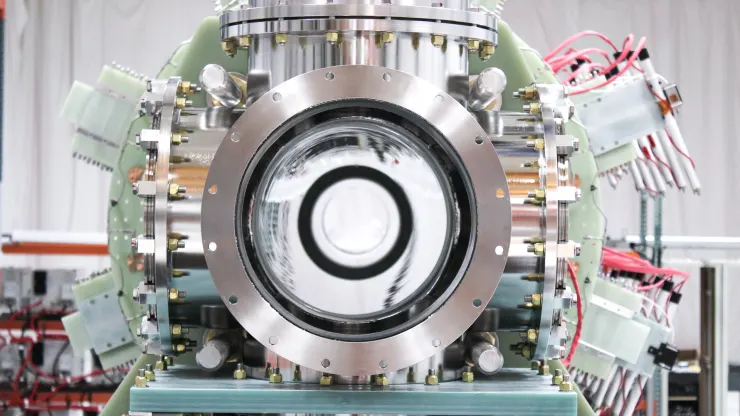

Helion has previously built six working prototypes and was the first private fusion company to reach 100m degrees C plasma temperatures with its sixth fusion prototype, Trenta. The company is currently building its seventh prototype, known as Polaris, which, it claims, will demonstrate the ability to produce electricity in 2024. However, in August 2021, Helion said Polaris would be completed in 2022. Moreover, although Helion has been able to generate energy with its fusion prototypes, like all most other fusion projects, it has yet to build a device that creates more electricity than it uses. The only facility so far to achieve this the US National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory using a laser-based fusion system.

Many other projects are based on donut-shaped device called a tokamak, such as the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) under construction in southern France, which is based on magnetic confinement of heated plasma. There are many tokamaks operating around the world. These include the Joint European Torus and MAST Upgrade in the UK, EAST in China, KSTAR in South Korea, T-10 in Russia, and SPARC a development of Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) in collaboration with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US.

Other magnetic confinement fusion technologies include Stellerators and Z-pinch facilities. A further approach to fusion is inertial confinement such as the experiment at NIF based on a process that initiates nuclear fusion reactions by compressing and heating targets filled with fuel. There are also a growing number of private companies developing different technologies, such as Helion.

Helion is building a long narrow device called a Field Reversed Configuration. This pulsed, non-ignition fusion technology involves shooting plasma from both ends of the device at a velocity greater than one million miles per hour. The two streams smash into each other, creating a superhot dense plasma, where fusion can occur. While many fusion approaches use deuterium and tritium as fuel, Helion’s fusion system will uses deuterium and helium-3 – a rare type of the gas used in quantum computing. Helion’s Polaris prototype is also intended to commercially produce helium-3 “for the first time ever here on Earth”, according to Kirtley.

Helion still needs design and construction approvals from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), as well as local permits. Andrew Holland, CEO of the Fusion Industry Association, told CNBC: “This is the first time that I know of that a company has a power purchase agreement signed. No one has delivered electricity, and Helion’s goal of 2028 is aggressive, but they have a strong plan for how to get there.” Helion CEO Kirtley topld CNBC: “This is a real PPA, so there’s financial penalties if Helion can’t deliver power… we believe we can deliver this power and are committed to it with our own financial incentives.”

He added that Microsoft and Helion have been working together for years. “The first visit we had from the Microsoft team was probably three of our prototypes ago, so many years ago.” He said announcing a contract now to sell electricity in 2028 “gives Helion time to plan and to pick a location in Washington State to put this new fusion device”.

However, a long article in Earther, part of the Gizmodo Media Group, was more sceptical about the prospects for Helion meeting its targets Helion was founded in 2013 and was helped along by an infusion of cash from startup accelerator Y Combinator in 2014. “That year, its CEO claimed that Helion could get a fusion reactor up and running in three years; two years ago, he said that the company would be able to generate fusion power and ‘go after commercially installed power generation’ by 2024…. It has now become the first fusion company to ink an actual power purchasing agreement for its services, and says that it will start supplying power to Microsoft in 2028 – more than 10 years after it initially said its reactor would be built.”

Earther spoke to Charles Seife, a journalism professor at NYU’s Arthur L Carter Journalism Institute and the author of Sun in a Bottle: The Strange History of Fusion and the Science of Wishful Thinking. “It’s so beautiful on paper,” Seife said. “That’s the appeal of it.”

Beyond Helion’s ability to perfect a process in five years that decades of research hasn’t yet gotten us to, there’s also a marked difference between advancing the science of fusion itself – which would alone be an incredible feat – and harnessing fusion for energy. A lot of the funding behind nuclear fusion in recent years in the U.S. has focused on achieving ignition, without an additional focus on creating usable energy from fusion; it’s a whole separate ballgame to actually put energy on the grid with the process. (Building a power plant alone is already a big infrastructure project that can take a couple years at best.)

“The classic joke is, okay, if you can produce energy, make me a cup of tea,” Seife said. “Once you make me a cup of tea, I will consider paying you money to do something, but first, make me a goddamn cup of tea.”

Image: Helion’s seventh prototype – Polaris – is expected to demonstrate the ability to produce electricity in 2024 (courtesy of Helion Energy)