Japan’s Kansai Electric Power Co said 22 December that it plans to decommission two 38-year-old pressurised water reactors (PWRs) at its Ohi nuclear plant in Fukui Prefecture. That brings to 14 the number of reactors facing decommissioning since the 2011 Fukushima accident.

Japan’s Kansai Electric Power Co said 22 December that it plans to decommission two 38-year-old pressurised water reactors (PWRs) at its Ohi nuclear plant in Fukui Prefecture. That brings to 14 the number of reactors facing decommissioning since the 2011 Fukushima accident.

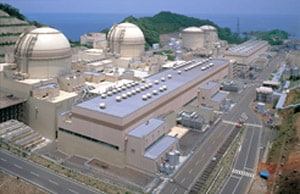

All but four of Japan’s 42 operable reactors remain shut, pending upgrades to meet new post-Fukushima safety standards. Ohi units 1&2, each 1175MWe, started operations in 1979 and were near the end of their standard operating life of 40 years. They have been offline since July and December 2011. Kansai Electric said that the costs of meeting the new safety standards were not a factor behind the decision, but technical difficulties were a problem. “The containment vessels of these reactors are smaller than other reactors in Japan, and the need to beef up the walls to meet the standards would make the work zones even more cramped, making it difficult for prompt repairs in case of troubles,” a spokeswoman told newspapers.

Ohi 1&2 are Japan’s only reactors with ice condenser emergency cooling systems. These use ice blocks in a basket installed around the containment vessel to rapidly cool the steam generated to reduce pressure in the event of an accident. In order to comply with new safety standards, the walls of the containment buildings would have to be thickened, narrowing the space between the containment vessel and the wall of the containment building. Kansai had estimated the cost of the safety upgrades at JPY830bn ($7.3bn). The Ohi units are the largest so far recommended for decommissioning.

Five smaller reactors were declared for closure in mid-March 2015. These include Kansai’s Mihama 1&2 (PWRs) Kyushu Electric’s Genkai 1 (PWR), Chugoku Electric’s Shimane 1 (a boiling water reactor) and Japan Atomic Power Co’s Tsuruga 1 (BWR). Shikoku Electric Power Company in March 2016 decided not to restart its Ikata 1 PWR. In addition, the six units at the crippled Fukushima Daiichi NPP and the four units at the Fukushima Daiini NPP are also scheduled for decommissioning (these are all boiling water reactors).

Monju closure

In December 2016, the government also formally announced its decision to decommission the idled Monju prototype fast breeder reactor (FBR) in Fukui Prefecture. The Japan Atomic Energy Agency in December 2017 formally applied to the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) for approval of its plan to decommission the Monju reactor. The plan was officially adopted in June by the government-appointed team to oversee the task. Decommissioning and dismantling are scheduled to be completed by 2047 and is expected to cost JPY150bn for disassembling the reactor and about JPY225bn in maintenance and management costs. The key measures include removing nuclear fuel from the reactor over a five-year period starting next fiscal year, followed by measures to eliminate the sodium used as a coolant.

The Monju FBR is now classified as permanently shut down and NRA has established a safety oversight team to monitor activities at the site. and cost $3.2bn (€2.86bn). Monju, a 246MWt sodium-cooled fast reactor designed to use mox fuel, reached criticality for the first time in 1994 but has faced a series of technical and other problems. It has mostly been offline since 1995 when 640kg of liquid sodium leaked from a cooling system, causing a fire.

Delays for Rokkasho

Shutting Monju could undermine Japan’s policy of nuclear fuel recycling which is also under pressure because of delays to the nuclear fuel reprocessing plant under construction in Rokkasho, Aomori Prefecture. On 22 December, Japan Nuclear Fuel Ltd (JNFL) pushed back the planned completion date by another three years, saying it now expects to finish the facility in the first half of fiscal 2021. JNFL noted problems with ageing equipment had forced the suspension of NRA safety checks. The deadline has been postponed 23 times from the original target of 1997. Work on the Rokkasho facility began in 1993, but two decades of delays have left many parts deteriorating. Rainwater leaked into a building housing an emergency power supply, and corrosion caused holes in exhaust pipes at a uranium enrichment facility, The Nikkei said.

Overall, Japan’s attempts to restart its nuclear power industry have been slow, with anti-nuclear campaigners and residents increasingly using courts to block restarts and push for plants to close. Residents have lodged injunctions against most nuclear plants across Japan.

Photo: Ohi 1&2 (Credit: KEPCO)